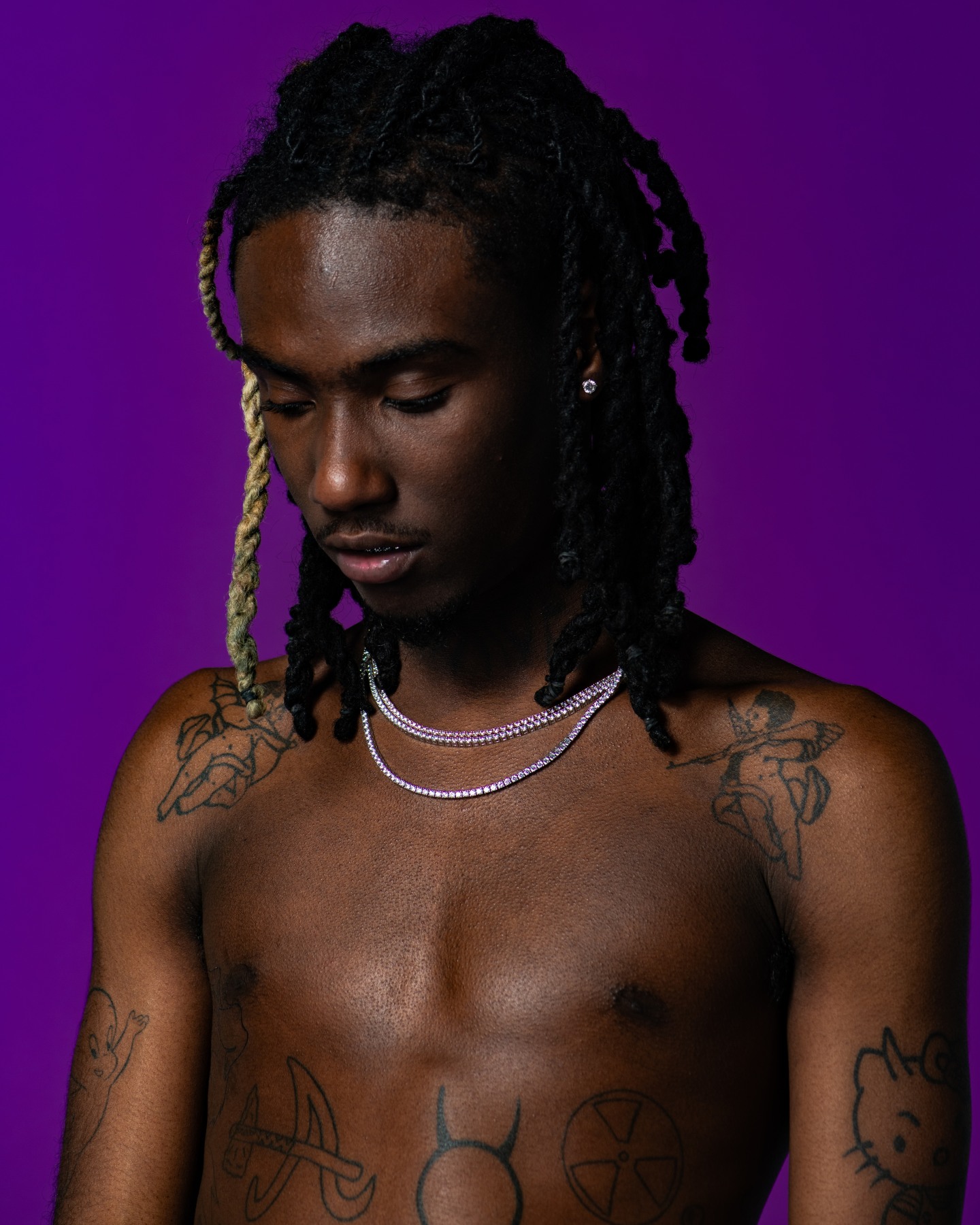

OsamaSon. Photo by GK

The only time OsamaSon stops smiling is when we talk about the leaks. 48 hours ago, the South Carolina rapper’s hotly anticipated third album Jump Out was unceremoniously dumped onto Telegram and Discord servers, spreading across the web and upending what had been a leisurely rollout.

“It’s super trash, bro,” the 21-year-old sighs on a Jan. 23 video call, smoking a blunt as his new spotted cat Flexer prowls the premises; a Christmas tree is still up in the corner of the living room. “I’m happy the fans are enjoying the music and I’m happy they want it so bad. But if they would give me a chance, I’d drop that shit… When y’all drop the shit for me, if I wanted to drop a trailer, if I wanted to go on live and preview it, if I wanted to do a music video, it all goes out the window.”

So instead of releasing on Valentine’s Day in three weeks, Jump Out is set to hit streaming platforms a little less than 8 hours from now. It’s a fitting-if-frustrating finale to a year of near-constant recording and refinement: previous iterations of the album leaked at various points in 2024, prompting loosie singles and tracklist overhauls. As much as any of hip-hop’s modern greats — Chief Keef, Young Thug, Playboi Carti — OsamaSon’s career has been defined by bootlegs. His unreleased songs are uploaded at an eye-watering clip, to the point fans joke his password must be “jumpout123”: last May saw a data breach of 400 songs at once. No mobile device in his orbit is considered secure. “Bro, n****s are really, literally hacking every phone I get.”

“Is it that serious?” OsamaSon’s eyes grow wide. “I guess it’s that serious.”

This may all seem mystifying to the uninitiated. The 2020s dominance of rage rap has enabled a whole host of Whole Lotta Red acolytes like Ken Carson and Yeat rapping over moshpit-instigating soundscapes defined by cataclysmic 808s and buzzsaw synths. The saturation has engendered a sort of sonic arms race, artists pushing on Carti’s aesthetic until their songs are harder, sharper, bigger. Differentiating between the various microstyles of the subgenre and its offshoots often feels like splitting molecules.

Where his competitors seem wholly fixated on imitating OPIUM’s style, OsamaSon intuitively understands the sound’s substance, how Chicago drill’s staccato flows and pluggnb’s digital liquid melodies and the distinctive 808 patterns of Philly tread have filtered down into the rage music of today. His July 2023 debut Osama Season was a mini-cult classic on arrival, building on the scene’s tones and tropes with tuneful instinct and an impeccable ear for beats, but December’s Flex Musix and its February 2024 deluxe FLXTRA showed Lil O and his producers were capable of more. From the meteor shower shimmer of “Rehhab” and the one-hit-KO kicks of “Trenches” to the lovelorn churn of “Kills” and the doleful melody of “Blonde,” OsamaSon’s sophomore album leaned on his knack for sticky hooks and deceptively simple flows to brilliant effect.

“Osama Season is so different because at that time, I didn’t really know what sound I wanted to go for — I was just rapping,” OsamaSon says. “The [producers] on Osama Season — boolymon, thrty, ok, perc40 — I’ve been working with them for years before I dropped that. I’m not saying I don’t try to work with every producer but these are my friends.

“Til this day, every single producer that’s on Jump Out, Draco and all of them, these are my friends. They done stayed the night with me, I done stayed the night with them, we done slept in the same bed. If we can build a friendship, bruh, I know we gonna be able to build a sound together, you feel? Something that can move the whole generation.”

OsamaSon. Photos by GK

Born Amari Middleton in 2003, OsamaSon grew up between Goose Creek, South Carolina, and Columbus, Ohio. “My parents were never together, so I used to just travel a lot back and forth. And it wasn’t too bad growing up. I wasn’t the richest, I didn’t get everything in the world, but I had clothes on my body and a roof over my head, so that’s all that really matters.”

Down in South Carolina, “all my uncles played musical instruments, so I was always around music when I was a kid.” What kind of music did they play? “It’s called Geechee music. And one of my uncles was into singing, so he was making R&B. It could have hit the masses, but unfortunately it didn’t.”

Eventually, OsamaSon’s uncle taught him how to lay tracks down in FL Studio. “I fell in love with [producing] and I just kept making beats no matter if they were good or not.” By the time he entered middle school, his summer vacation was consumed by sessions in a DIY backyard studio. When I ask about his early production, he names GLOhan, specifically citing the producer’s trap flips of video game soundtrack samples.

“Once I got into high school, I started making Chief Keef-type beats, NLE Choppa-type beats. Then it evolved. It went from that to me hearing Summrs and Kankan and I started making those [pluggnb] type beats.”

OsamaSon started rapping on his own production because nobody else would. “I feel like that era was some of my most creative times, but it was some of my hardest times too, cuz I was going so hard. I was creating these beats and I’m rapping on them and I’m mixing everything and I’m finalizing everything but it wasn’t getting no attention at all.”

His voice lowers. “It made me want to go harder though, for sure. But it was pretty rough, I’m not going to lie. Just feeling like you’re going so hard and you’re doing the best you can, bro. And nobody’s acknowledging or seeing that shit. It gives you the worst feeling of all time cuz it makes you feel like, am I not meant for this, am I not good enough?”

These days, OsamaSon has more eyes on him than he can sometimes handle. Online, his teenage TikToks, high school journalism classwork, and childhood photos have been widely disseminated, leaving him bemused and privacy-oriented. “I made those TikToks to try to go viral, so I can’t be mad at that. But when it comes to the high school [news reports], I don’t know how they getting that shit. I damn near forgot I did that shit.”

“I know it comes with the fame, but it shouldn’t have to be a requirement,” OsamaSon groans. “Y’all don’t have to go dig personally through my mom’s Facebook just to see some baby pics of me. Maybe I’ll drop my own baby pics!”

“If we can build a friendship, bruh, I know we gonna be able to build a sound together, you feel? Something that can move the whole generation.”

Still, the pros certainly outweigh the cons.”Sometimes I get drowned in the negative shit cuz who doesn’t? Especially when people are talking about you 24/7. But I’m still blessed and grateful to be in the spot I am, cuz it was bad — my friends wasn’t even supporting me,” he laughs. “But I still feel like even with where I’m at now, I want a lot more. I want the whole world to know about me.”

Executive produced by North Carolinan wunderkind wegonebeok, Jump Out finds OsamaSon broadly pivoting away from the dark plugg sound that shaped his first two albums as well as collaborations with tdf, boolymon, and Glokk40Spaz. “Once it gets too easy to a point where I’m making songs in five minutes it’s just like man why would I keep doing this? Why would I just keep making the same song over and over again?” OsamaSon explains. “I just felt like it was time to evolve from that.”

Later on, when we’re discussing video games, OsamaSon will mention that he loves playing the 2011 hit mobile game “Jetpack Joyride” on his jailbroken iPod Touch — “I use the bubble [jetpack] because I don’t be trying to hurt the people.” That image feels like a perfect microcosm for Jump Out, which sparkles, soars, and shines at every turn, a delirious blitz of fast money and cartoonish powerups.

Other rage albums aim for maximum carnage to pummel listeners into submission, but Jump Out opts for melodic euphoria, swinging back towards the bright toplines and smooth bounce that animated much of Pi’erre Bourne’s work on Playboi Carti and Die Lit. Consider the giddy spiral of checking account statement “Break Da News” or the nonchalantly skyscraping “Insta,” where a girl is so cute Lil O can’t even be mad over her thirst traps; skai’s seething backdrop for “New Tune” kicks OsamaSon’s flow into sport mode, and he delivers some of his catchiest choruses ever on “I Got The Fye,” “Fool,” and “Made Sum Plans.” It’s hard to mind the lightweight subject matter when his energetic vocals make even the heaviest beats levitate.

wegonebeok is likewise at the peak of his powers on Jump Out, producing 15 of the album’s 18 tracks. The discordant pan flutes on “Room 156” sound like someone threw “Magnolia” in a wood chipper, and the wobbling 808s on “Going Dumbo” are somehow perfectly translucent; whether a song is 10 seconds from nuclear implosion (“GTFO The Room”) or gently fizzing like a Barq’s red creme soda (“Jumpout”), these instrumentals make the burgeoning producer’s past work for Nettspend, Glokk40Spaz, and Izaya Tiji look like type-beats of himself.

These are still very loud songs (see: the glass-shattering “Mufasa”), but where previous records burst at the seams with countermelodies and adlibs, the tracks on Jump Out are more focused and direct, every sound effect considered and leveled just so. OsamaSon credits the shift to his new recording process with engineer Moustafa Moustafa: “I started hopping in the studio with an engineer, and that right there completely changed it, from the mix of how I sounded to the way I was punching in to the hooks being longer, the verses being longer, shit being more structured and not just all over the place.”

What have you been focused on sharpening? OsamaSon chews it over. “What I rap about to be honest — and how I go about saying certain shit. I remember a long time ago, somebody was clowning somebody cuz they was like, every bar he says, it starts with ‘I’. And I was like, ‘Damn, let me listen to my music,’” — he smirks — “And I was saying ‘I’ for every start of the bar, like I get bitches, I get money…

“It’s just certain shit I had to critique myself on, and just change, even when it came to my adlibs bro. I used to go way too overboard with my ad libs — I had to learn to either keep it simple or don’t even do ad libs at all, cuz I can’t take away from the main vocals. And then with my verses, just really making sense. That’s really what it is: I make a lot of sense in this shit, I feel like a lot of people can relate to either what I’m saying or they can feel that shit.”

“I want anybody to hear my shit — I like this song. I’ll bump this on repeat, from if you’re one years old to if you’re fucking 199 years old.”

He’s hoping the attention to detail is noticed by a wider audience. “I hear a lot of people be like, ‘Yo, I played it for my parents and they were like, Yeah, I’m not really rocking with it, but if that’s what the kids listen to, then it’s lit.’ I don’t want that reaction no more,” OsamaSon tells me. “I want anybody to hear my shit — I like this song. I’ll bump this on repeat, from if you’re one years old to if you’re fucking 199 years old.” Later, when I ask about his goals for the album, he’s almost wistful: “I hope it really changes the perception of me.”

What’s the perception of you right now? “I feel like they don’t think I’m versatile enough; I don’t really think they feel like I’m rap, you feel me? I feel like they think it’s just loud noises and good feelings. But now it’s good feelings, good lyrics, good beats; it’s not just one specific thing pulling people to my music.”

OsamaSon is already a Gen Z icon, although he’s far from satisfied. When pressed if he has specific career goals or milestones that’ll tell him he’s finally made it, he’s bullishly vague and sunnily confident.

“Nah, I probably wouldn’t know until I die or some shit honestly. I don’t think I’mma ever be done,” OsamaSon shrugs. He pauses, then shakes his head a little. “Cuz it’s people who done went so brazy in life — I was like, All right, how can I go even brazier than them?“