As I watched the prologue of In Whose Name?, a new documentary on the rapper and producer Kanye West, one question ran back and forth through my mind: Could it have gone any other way for him?

The film begins in the halcyon days of West (now known as Ye)’s career, when he was one of the biggest artists in the world, massively commercially successful and heralded as the future of music and fashion. A procession of artists and celebrities seeks Ye’s favor or otherwise regard him with awe. Lady Gaga uses her desire for Ye’s fame to inspire the design of their (eventually cancelled) joint tour. Diddy is lost for words after a performance. Pharrell compares him to Michael Jackson. The segment ends with Ye drunkenly hacking up a sneaker-shaped birthday cake with too few people telling him to stop. The writing may have always been on the wall.

Fame, Ballesteros’s documentary suggests, can swallow anyone whole; two decades after that scene was filmed, Ye had destroyed his career and reputation. I had no interest in watching this film when it was first announced. I have followed Ye’s antics closely since 2016; I was disappointed by his simpering embrace of Donald Trump, disgusted by his declarations of “slavery was a choice” and “White Lives Matter,” and horrified when officially declared himself a Nazi. I didn’t know it at first, but I was watching the real-time effects of the “red pill,” where consumption of far-right political content leads to an embrace of toxic and hateful ideology. That this change was taking place in one of the most revolutionary Black artists of all time made him a potent propaganda tool to be paraded by right-wing talking heads like Candace Owens and Alex Jones, and for a time, the president himself.

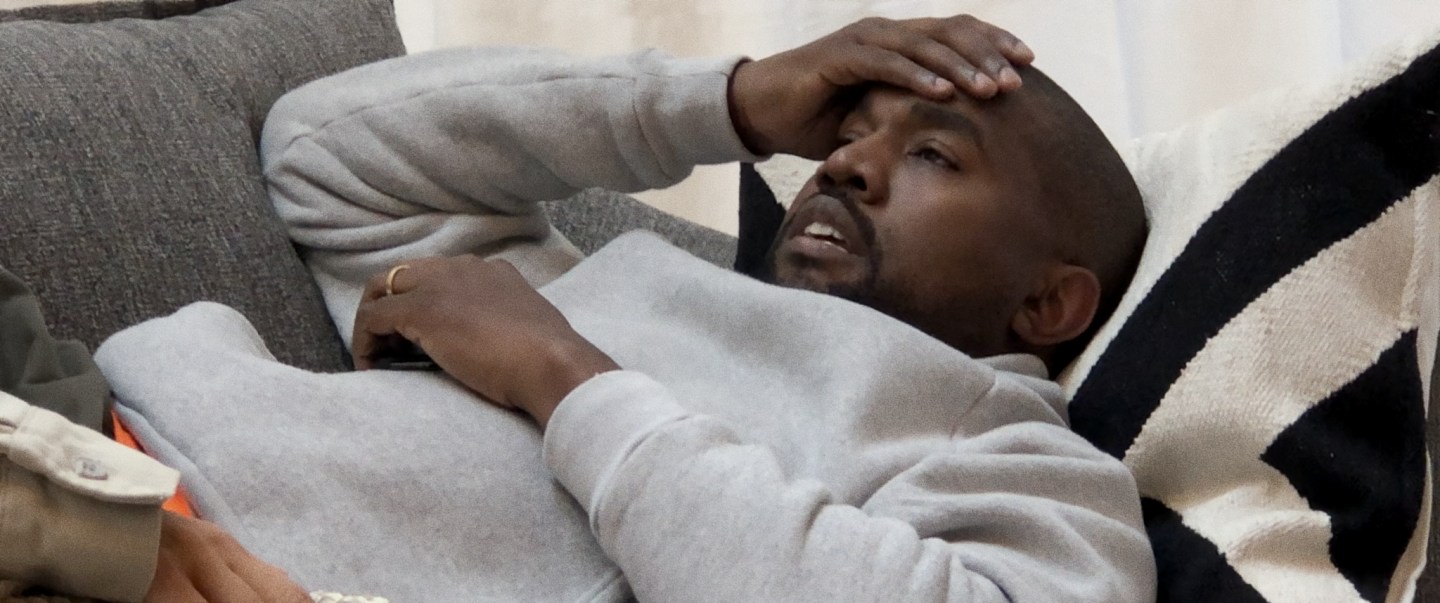

But Ballesteros’s documentary weaves the familiar trainwreck into something beyond mere spectacle. Now 26-years old, Ballesteros spent six years recording thousands of hours of footage in his capacity as Ye’s official videographer, beginning soon after Ye was hospitalized following a breakdown (he’d later be diagnosed with bipolar disorder). A documentary seems to have always been the goal, and Ballesteros opts for an observational lens, shadowing Ye around the world in meetings, studios, and at home. His mental health dissolves over the years as he desperately seeks to build his empire and escape mental slavery, both pharmacological and cultural.

There’s a preponderance of media seeking to decipher Ye, from podcast interviews to YouTube documentaries. Ballesteros’s film distinguishes itself with threadbare, efficient narrative and canny editorial choices. Netflix’s vaguely evangelical three-part West documentary jeen-yus suffered from bloat and didactic voiceover; In Whose Name? is lean and does not overtly impose itself on viewers as it tracks Ye’s downfall with a combination of never-before-seen and widely circulated footage. In one case, we see Ye’s 2019 Saturday Night Performance, where he insulted the cast and crew; backstage afterwards, he shrinks when checked by a visibly upset Michael Che.

What In Whose Name? shows us of Ye humanizes him without inspiring sympathy. The effects of his abominable selfishness are most clearly seen on his then-wife, Kim Kardashian. From a tent in Uganda to their home in Los Angeles, Kardashian tries her best to manage her husband’s ferocious outbursts, usually dissolving into tears. His ambitions — political, religious, creative — are picked up and dropped with dizzying speed, usually leaving something broken behind. “The best thing about being bipolar and an artist,” Ye says at one point, “is that everything you say and do is an art piece.” Is he out of control and desperately searching for meaning, or lazily slapping a Warhol-esque label of “art” onto his vicious bigotry? In Whose Name? presents questions rather than answers them. Is Ye making a bold creative decision or a cowardly one?, the film asks.

Ballesteros has discussed his affection for his subject (he called West “kind of a mentor” in an Los Angeles Times), and Ye enjoyed the finished film (though he reportedly did not have final cut). His approval is relevant in light of the more than dozen lawsuits he faces from former associates and employees with allegations including sexual abuse and racial discrimination. The movie has no indication that Ballesteros was filming during any of the alleged incidents, or shows West exhibiting any similar behaviour; we don’t see anything quite as shocking as West screening pornography for Adidas executives, something West included in the 2022 short doc Last Day (and is mentioned in at least one lawsuit against West). It’s difficult not to wonder if more incendiary footage exists and was deliberately not included to create a less thorny version of Ye.

What’s undeniable is that, thanks to the KKK outfits and the swastika shirts, decoding what’s true about Ye feels like a futile task. The saddest thing is that may have been the case for far longer than we’d like to admit. Early on in the film, Ye uses the phrase “method acting” to describe his performance in the documentary as Pharrell nods on a couch. And for most of the film there is a vague discomfort on his face, like he’s aware of the camera’s presence. It’s only when he’s wearing a prosthetic cat mask that you can see his face soften even under the makeup and deeply pixelated image. “I’ve suffered so much trauma in my life,” Ye says. For once, it’s not an excuse. It’s just him in the backseat with Ballesteros; for a moment, it feels like fame can’t get them there.