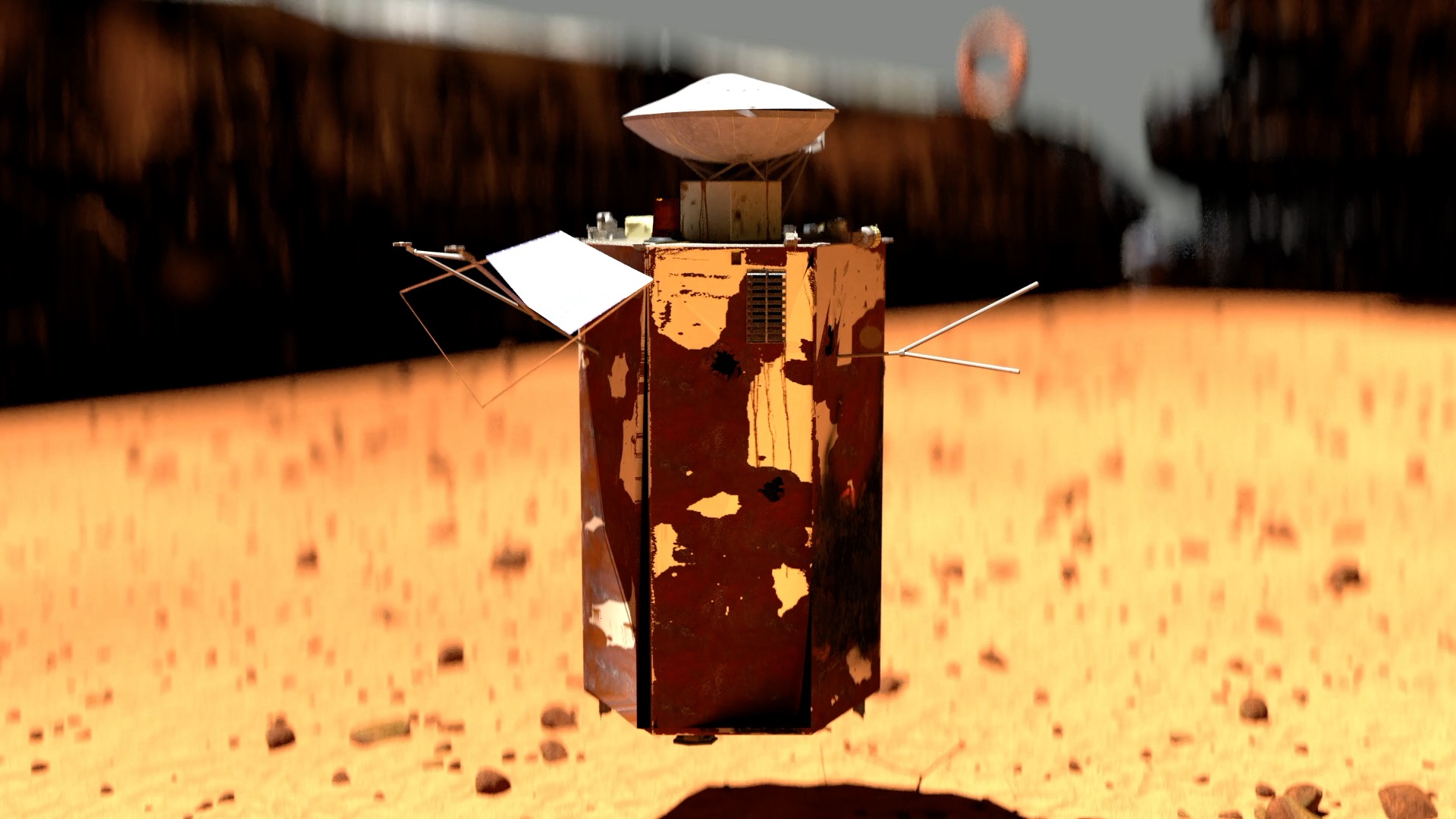

Samuel Beckett meets Groundhog Day meets Pinocchio, set against a digital simulacra of the Tabernas Desert in Almería, Spain.

“Young Billy is standing, he is trying to remember. Standing so fine, all painted and shining, with his sailor’s cap. He should watch out for sunburn of course.” So begins Billy Takes A Break, a short from multidisciplinary artist Jack Jelfs that bundles together a miscellany of disparate references, including the infamously dense ideas of Deleuze & Guattari, the equally daunting novels of Samuel Beckett, Harold Ramis’s Groundhog Day and a formative Tarot reading, laying them out in a computer-generated approximation of the

Tabernas Desert, located in the Spanish province of Almería. “The desert was used as a stand-in for the American southwest in a bunch of Spaghetti Western cowboy films made in the 60s and 70s, the term “spaghetti” refers to the Italian origin of many of the directors of the films, but most of the actual shooting locations were in Spain,” explains Jelfs. “There are even a few surviving film sets from that era that are now tourist attractions, with names like Fort Bravo and Western Leone. Something about the artificiality and incongruity of these fake towns, dry and dusty monuments to the illusion of cinema in the middle of the Spanish desert, really stuck with me.”

It’s this dichotomy between functional artifice and dysfunctional emptiness that the artist plays with throughout the course of the short. Billy, a gravity-defying contraption seemingly bolted together from rusted sheet metal, bent aerials and a satellite dish that does bear a passing resemblance to nautical headwear, is trapped in spatio-temporal loop by a disembodied narrator preoccupied with trying to define exactly what Billy is, oftentimes with complete disregard for Billy himself. “Billy is rotating,” says the voice, as Billy floats motionless. “Billy is covered in fog,” the voice attempts to claim, as a Spaghetti Western sun beats down on his metal exterior. In this way a tension develops between the narrator and the images we are presented with, as Jelfs zooms out and manipulates the digital topography of the piece, throwing the very parameters of the short into question. “I like works of fiction that knowingly point to the fact that what you’re experiencing is fiction,” he says. “I was thinking about Beckett’s trilogy of novels (Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnameable) in which every character is a fictional creation of another, and all are ultimately trapped in their fictional condition. I’ve always loved the stories of Philip K. Dick too, which are never afraid to pick at the ontological boundaries of their worlds and characters.”

“Also in there somewhere is the story of Pinocchio,” Jack Jelfs continues, “the weird father-son relationship between Geppetto the puppet-maker and Pinocchio, the wooden boy he builds – who seeks an impossible transcendence from the limitations of his material condition.” A strange animosity develops between the narrator and Billy, with the disembodied voice describing “his little puppet head” and “his arms of string”, before sinisterly asserting: “he should watch out, if he knows what’s best.” It was from Jelfs’ dalliances with Tarot readings that the more menacing quality of Billy’s back and forth with the narrator became more developed. “I think the final influence came from doing a few tarot card readings early on in the process of developing the ideas,” the artist recalls. “From the Wheel of Fortune came the idea of being stuck in a Groundhog Day-like loop, the same situation repeating over and over.”

“The other important card was The Devil,” Jelfs explains. “I think that the voice, and maybe the landscape and computer-generated environment itself, are all aspects of some demonic force that keep Billy stuck there.” We bear witness to a kind of ontological torture that the narrator subjects Billy to when we are shown that Billy’s body is indeed hollow. “This house is empty,” asserts the narrator, thrusting functionality upon the negative space within the confines of Billy’s metal borders, before inserting said functionality into Billy-as-entity, “and here’s old Billy, standing so fine, all painted and shining,” before whipping Billy’s function and subjectivity out from under him, leaving him “an old, flattened ghost.” As the tension builds so too does Jack Jelfs’ score, which builds up speed as a galloping cowboy theme, tripping up over itself in rapid loops that glitch and stutter, continually deferring any euphoric release, leaving us trapped in built-up potential alongside poor Billy. “This is hopeless,” the narrator emphasises, “Billy looks sad.”

“From all of this came the figure of Billy,” concludes Jelfs. “A floating signifier (literally floating) and an empty, inanimate body, who’s stuck somewhere between a sci-fi film and a Spaghetti Western, jerked around like a puppet by an invisible agent, and inescapably trapped in both time and space. I’m not sure what he achieves at the end, if it’s death or transcendence or just a break. Whatever it is, it can be undone by just playing the film again.”

For more information about Jack Jelfs you can follow him on Instagram and visit his website.

Watch next: C2C Festival X Fundaciòn Marcelo Burlon Present: Arca & Weirdcore, Live From Ibiza