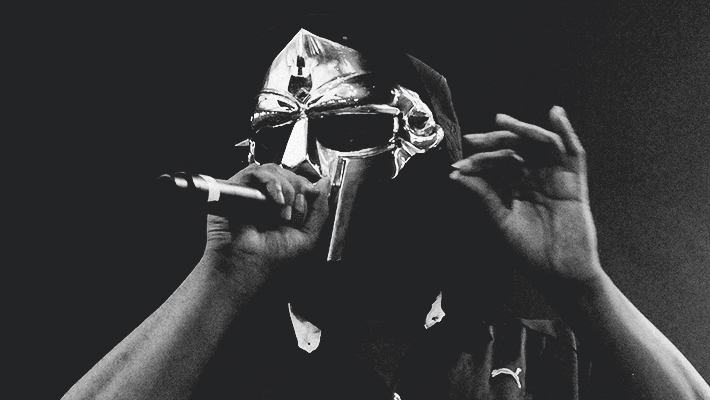

Where do you even start to eulogize MF DOOM, whose October 31st death was revealed on December 31 by his wife? Set aside the decades-spanning career and multiple personas, from Zev Love X of KMD to Viktor Vaughn and King Geedorah. How do you even begin to encapsulate his impact? Sure, in the last few years, the Rap Twitter convention has held that he was the vanguard of uber-cerebral, anti-establishment hip-hop that “scares the girls away.” But as with so much social media “wisdom,” that reductive outlook was never the case.

MF DOOM didn’t appeal to only rap nerds — you’d be hard-pressed to find even casual rap fans who hadn’t encountered and subsequently been entranced by his rhymes and his persona. His influence within the culture was so widespread that it didn’t seem beyond the realm of possibility that even an affluent white lady actress like Sharon Stone would be a fan. His flow was impeccable, respected by rap purists and SoundCloud rebels alike. It’s impossible to gauge how heavy his impact was, simply because everyone knew about him, but everyone who knew about him felt like he was their personal secret.

He was a traditionalist and he pushed the boundaries of how the genre could or should sound, beginning with his time as a member of early ’90s trio KMD. He could be frustrating, as Adult Swim Vice President Jason DeMarco learned more than once. He could be exhilarating. He could be inspirational. He was an example of hip-hop at its most extravagant, but he was surprisingly ordinary. That was the point of the mask; he could break kayfabe at will, yet he could also be forgiven for leaning way too into it by scamming fans into paying to watch imposters perform his songs, like a true supervillain (hey, even Doctor Doom has his Doombots).

So how could I possibly sum all that up in even a 500-page book, let alone an 800-word internet article? I guess I could start with how much MF DOOM meant to me personally, those late-night adventures with the crew in my late teens/early twenties cruising the streets of Los Angeles blasting Madvillainy and Mm..Food at maximum volume. Or going even further back, to those all-day rap forum rabbit hole sessions, tying up my family’s phone line downloading Operation Doomsday on dial-up. Or the thrill of excitement I felt realizing that yes, that was his voice booming over Cartoon Network commercial bumpers and scenes from The Boondocks.

But somehow relating this all seems too mundane to capture DOOM’s import. After all, there are likely hundreds of thousands of hip-hop fans with stories just like it — a supreme irony, as we all felt like the only ones in the world who were in on the secret of the masked rapper’s existence. Biographing him doesn’t seem like enough, either. With a career that encompassed a prime placement in hip-hop’s Golden Era, bridging the genre’s bumpy entry to the online age, and maintaining his air of mystery along with his authenticity while experiencing the heights of his commercial ubiquity with Adult Swim, there’s just too much there to unpack and examine.

He did all that though. He was one of the first rappers to appear on broadcast television, on The Arsenio Hall Show, performing alongside 3rd Bass as he rattled off his ahead-of-their-time rhymes on “The Gas Face.” He is arguably the symbol of the Napster generation of rap, his projects being among the first to trickle outward from college dorms through person-to-person sharing across state lines and high-speed connections to spread his legend. And though their partnership never came to fruition — mostly because of DOOM’s propensity for vanishing for years at a time while dealing with personal issues — he was one of the first rappers to sign with Adult Swim’s music label arm, Williams Street Records, paving the way for future collaborations such with rap luminaries such as Witchdoctor, El-P, and Killer Mike, catalyzing the connection between the latter two to form Run The Jewels.

DOOM influenced heady, introspective rappers like Earl Sweatshirt and Jay Electronica and rap establishment-trolling rabble-rousing South Florida upstarts like Smokepurpp and Wifisfuneral. Playboi Carti, who many underground rap heads regard as a cancer to the genre, paid just as respectful a homage as elder statesman Busta Rhymes. DOOM could work with any of his peers, like Ghostface Killah of Wu-Tang Clan and fellow multiple-personality MC Kool Keith, but that didn’t stop him from granting his blessing to rising young stars like Bishop Nehru, with whom he crafted a pair of projects, one as a rapper and one as a producer.

I’d be remiss not to mention his pioneering production style, which has proliferated on YouTube through adherents to the “lo-fi/beats to study to” aesthetic that permeates playlists from the likes of Chilled Cow and College Music. Hip-hop and animation now go hand-in-hand, from the Vince Staples-starring Lazor Wulf to the music’s subtle nods in shows like Big Mouth. If you think MF DOOM isn’t one of the biggest reasons why… I’ve got a bridge in Brooklyn for sale. DOOM’s influence, his impact, were as far-reaching as his vocabulary, which included references to volcanoes in Iceland and the chemical name for ecstasy, and yes, he found equally elaborate rhymes for both.

All of that only covers a bare fraction of who DOOM was, how innovative he could be, how true to the art form he was. It doesn’t reveal anything about the man himself, who so staunchly separated the persona from his true identity that collaborator Count Bass D once recounted observing self-declared DOOM superfans discount their hero’s very existence upon encountering him in person sans mask. DOOM was a father who lost a son, a man who lost a brother, an artist whose career ups-and-downs informed an adamant lifetime philosophy of never playing by the rules and constantly upending the mechanisms of commerce, even to the chagrin of his business partners, collaborators, and fans — sorry, gang, but we are never getting that Ghostface/DOOM collab album.

Even the way we found out about DOOM’s death, two months after, on the final day of 2020, like a bookend or a coda to the disastrous year that was, like he’d ensured that the blow would be held back to close that horrendous chapter as resolutely as possible… even that was DOOM being DOOM. To the very end, he was getting the last laugh, upsetting the balance with his theatricality, and ensuring that no one could ignore him, forget him, or dismiss him. He was our hero even though he was, to the very end, a supervillain.