In this career-spanning interview, originally published in the A/W issue of 2020 Fact’s print edition, Ryoji Ikeda details his thought-provoking universe of immersive digital art.

Ryoji Ikeda’s innovative work explores the essential characteristics of sound and light by means of mathematical precision and aesthetics. By orchestrating sounds, visuals, materials, physics and mathematics, Ikeda goes beyond the conceptual to delve into extremes and infinites, testing the limits of human senses and digital technology.

Ikeda’s long-term projects have taken a multiplicity of forms, from live performances and immersive audio-visual installations, to books, records and CDs, and have evolved over the years to encompass the latest iterations of his data-driven research. His work has transformed the way we experience art and pioneered a global movement with immersive works that push our senses to new sonic and visual extremes, challenging our understanding of the universe and our place within it.

In 2021, Fact and The Vinyl Factory presented one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of Ikeda’s work to date at London’s 180 Studios. The exhibition featured 12 large-scale, multi-media works, including six global premieres. Imagined by Ikeda as a subterranean exploration of sound and light, the exhibition took viewers on a sensory journey of 180 Studios’ labyrinth-like spaces, which seem to defy the building’s scale.

In this career-spanning interview, originally published in the first issue of Fact’s relaunched print magazine in 2021, Ikeda speaks to Hayward Gallery director Ralph Rugoff about the show and his practice as a whole, offering rare insights into works such as test-pattern, point of no return, and his data-verse trilogy, a body of work that visualises and sonifies the different dimensions co-existing in our world, from the microscopic, to the human, to the macroscopic.

Ralph Rugoff: Your show at 180 Strand brings together a variety of very different works, from subtle sound installations and minimalist light works to spectacular video projections. When designing the exhibition, did you conceive of it as a single composition with a certain flow?

Ryoji Ikeda: I’m basically a composer, so my job is to compose something. So I compose the placing and pacing of the exhibition in response to the nature of the physical space. The entire exhibition is based very much on physical experience, not only intellectual content. It begins with works that give intense, very simple experiences, and then the works get more complicated, like the data-oriented digital projections such as data-verse.

It’s a kind of orchestration of 12 large-scale installations. I also tried to make a balance between the sounds from the different installations. In a group show, managing sound bleed can be very difficult, but in a solo show it’s nice to have a mix of soundscapes that you can hear at the same time. It’s a fantastic opportunity. I can even recompose soundtracks of different works so they work better together.

You’ve also included a number of silent light installations in the exhibition, which create a range of very distinct experiences. Can you tell me about your new work in the show that makes use of laser light?

Nowadays many artists are using lasers in very spectacular ways, but I don’t do this – this is a very straightforward work. In a small black box space, a laser device on the ceiling, projects very simple scanning lines onto the floor. A glass wall divides the laser light from the visitor. Because everything is painted black in the box, the laser lines will appear as if floating in space. So the feeling is like observing something in a laboratory that’s seemingly a little bit dangerous – something inhuman, a very cold expression that you are invited to observe and analyse.

point of no return, a very different kind of light installation which comes a bit earlier in the exhibition, seems to offer a more subjective type of experience.

point of no return is a very simple, very intense piece. I paint a black circle on a wall and project light around it, and this intensifies its blackness. It feels like it’s always firing, you get a bit scared. It becomes a bit overwhelming. The other side is the total reverse, just a white circle. It never changes, just stays still like a moon.

So the piece is completely abstract and people can interpret it however they like. All of my work is open like that. But a circle can represent infinity; it’s like a Platonic sphere, something very pure like planets and stars.

Or a black vinyl record?

“Point of no return” is actually a term used by astrophysicists. It’s like the event horizon of a black hole, the point at which you can’t escape its gravitational force.

Astrophysics play a part in the exhibition’s central installation, which features three digital projections data-verse 1, data-verse 2, and a brand new iteration, data-verse 3, which completes the trilogy. Using open source data sets in a series of ‘verses’, these works progressively chart the physical world from sub-atomic phenomena to a map of the cosmos.

It’s a bit like the film Powers of Ten by Charles and Ray Eames, but the scope is much, much wider. In 11 minutes, you go on a journey from micro scale to the scale of the universe.

Usually I visualise scientific data relating to very small or very big things. But here, for the first time, I included some data related to human scale, ranging from proteins to anatomical parts to cities.

Shown together as a single installation, these three works must surely comprise your most complex project to date?

This is the premiere of data-verse 3, and it’s also the first time that I show all three works together, and it may be the last time as well because it’s very difficult to set up. But the three works are very well balanced. It’s kind of like a symphony orchestra. Everything is perfectly synchronised.

Is there a single soundtrack for all three projections?

It’s very slightly different for each one. It’s the same timing, same composition, but slightly different content.

In the past you’ve said that sound should never be a slave to the image, but in this trilogy the visuals — all that dizzyingly complex data – seem to take precedence.

The sound is not a slave in this work, but it’s kind of a navigator of the visuals. If the sound is too rich with this kind of work, it’s simply too much so I tried to be as minimal as possible. But for me, there’s no separation on one level between sounds and visuals. When I start a new work, it’s all just an operation of a particular structure. So I still feel that data-verse is very much a musical composition piece.

Did your initial thinking about data-verse take root during your 2014 residency at CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research based in Geneva?

I have a good relationship with CERN, which is the mecca of particle physics. For two years I had a key that let me into every laboratory. I could talk with the scientists there, exchange questions and ideas and I really learned a lot. What they’re doing there is really extremely beautiful. And some part of data-verse did come from their data and also their aesthetic. Everything that they explore there is totally invisible, it’s on the subatomic scale. But whatever experiments they undertake, and whatever difficult theories they develop, the point is always to try to reveal the mysteries of nature.

As it cycles through vastly different orders of magnitude, data-verse inevitably calls attention to the limited character of our everyday ‘human-scaled’ perception. In this respect, it reminds of your earlier (and ongoing) interest in pushing the limits of what is normally considered music – such as using white noise or sine waves, or sounds beyond the range of human hearing. What is it that draws you to these kinds of sonic materials?

Of course I’m interested in mathematics and quantum physics, but that isn’t really the starting point for me. I began my career working with a Japanese multi-media art collective called Dumb Type. The group formed in 1984, and over the years it has done many performances and installations around the world. Altogether there were like 15-20 people involved, from completely different types of backgrounds. I’m still kind of a member. The theme of their work is always related to social issues. I was of course interested in composition, video and technical matters but I learned a lot about social and political contexts through my work with them.

Dumb Type toured internationally and wherever we went audiences and critics perceived us as “Japanese,” even more so than as artists. And they put this label “Zen” on everything. I was not really happy about that kind of labelling. So I became interested in making my music as universal and transparent as mathematical equations. Maths is not like culture – there’s no such thing as Chinese or African mathematics, for instance, because science is concerned with universal facts.

I wanted to make something like this through music. So I decided, okay, I would use pure tones, sine waves, white noise – these are materials that everyone can use. For my CD +/- (1996), I made music only constructed with sine waves and white noise. But after +/- came out, people said, ‘Oh, this is so Zen, so Japanese!’ (laughs). So I learned that you cannot really escape this labelling very easily.

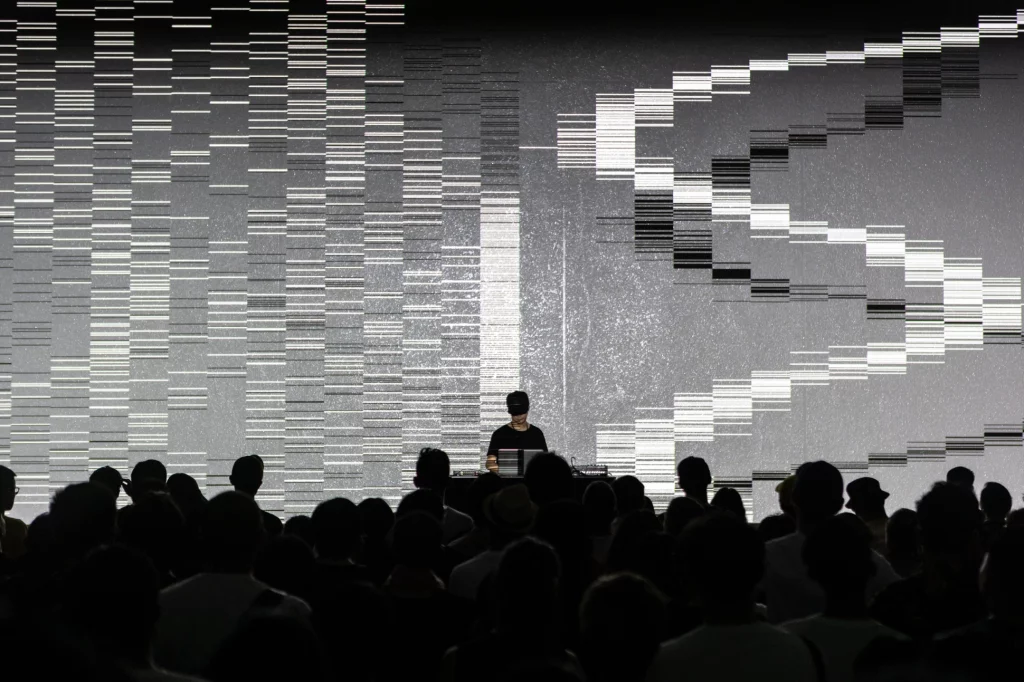

You’ve decided to end your exhibition with the audio-video installation test pattern, which I can’t imagine many people would describe as being “so Zen.” It’s more like entering a throbbing nightclub dedicated to bar codes.

Test pattern is so loud that it’s like a concert. It’s very physical and abstract. The soundtrack is a sonification of pure data, it’s very brutal, very strong. With data-verse, you observe various phenomenon from an exterior perspective, but with test pattern you dive into the experience. You are tested, you have to jump in. The big digital projection screen shows tiny data bits that have been totally enlarged, like under a magnifying glass, so the expression is binary, just zeroes and ones. But data has really beautiful patterns, even the data embedded in your emails and photos.

Your exhibition spans a disparate range of approaches to making art and music. Do you develop the ideas behind distinct types of work in different ways?

First of all, I’m never working on just one project. I’m more like a painter who’s working on several canvases at the same time. When you stick to just one project, you get mad. You try to put all your ideas into this single work and it becomes too much. I much prefer working on many things at same time.

I remember visiting you at 180 the Strand in 2019 when you were finishing work on data-verse 1. It was such an intense atmosphere in that room! It felt like a kind of a performance, a dress rehearsal with you conducting your team of five programmers who were tweaking digital codes for the images and music that were playing.

The production of data-verse took place over two years. When you visited us, it was the last stage – the composition was already complete and we just had to work out minor changes. So at that point I’m like a conductor or a director. But each project has a completely different composing process. I’ve been working with the same programmers for many years now, and they are like collaborators, not just assistants. It’s like a band – who’s taking care of the drum, the bass, the guitar, a bit like this. I make a master plan, but usually we discuss a lot and many ideas come from them.

One of the advantages of taking a long time to make work is that it gives you more chances to reconsider things. Sometimes in the middle of the process, we unexpectedly turn left or right, do something in a different way, and the project goes in a new direction. It happens many times.

Do you create a score for your compositions?

To make a score is really my job. Not every production has one, but data-verse, for example, has a huge score in the form of an Excel spreadsheet. I write down texts, signs, function equations, memos, research. I also include jpegs and website links. It’s really like a kind of cookbook. When I make a performance piece, I also create an enormous score.

While they are rigorously composed, many of your works also incorporate elements of noise.

In classic information theory, it’s said that to verify the signal we definitely need noise. It’s a complementary relationship. That kind of concept is still really interesting to me. Humans love to organise things so we often hate randomness. To me, though, randomness is a hint of the richness of our lives. It’s not something to be thrown away.

That play between order and randomness has been central to a long tradition of avant-garde music and art.

For me, music is structure plus sound. Even in John Cage’s pieces that are seemingly unstructured, there is a structure. You need a certain set of rules, or structure, which is a property of mathematics. Sound, on the other hand, is a property of physics. It’s just vibrations of the air. So sound plus structure is what makes music for me. Both pure composition and actual physical phenomena are very important for me.

I think that’s apparent in how your work is highly conceptual and abstract on one level, and yet is always open-ended in a manner that emphasises the experience of the viewer.

I don’t like the overly intellectual orientation of some contemporary art. I’m a musician basically. And we don’t think in that way. We play music, and of course there’s some intellectual concept or theme always, but it’s not that important. What you hear, what you experience – that’s everything, whether you’re at a live performance or listening to a recording. Music is beautiful because we can’t see it and we can’t touch it, but everyone knows it. You don’t need to have it explained; you don’t need special tools to understand it. You can charge it with meaning all by yourself. That’s the same approach I take with my installations.

Introduction by Sean Bidder

Interview by Ralph Rugoff

This interview was originally published in Fact’s Autumn/Winter 2020 issue, which is available to buy here.

Fact × The Vinyl Factory presented RYOJI IKEDA in collaboration with Audemars Piguet Contemporary, at 180 Studios, 180 The Strand, 20 May 2020 – 18 September 2021.

Watch next: Caterina Barbieri: light-years